To the teeming multitudes of his adoring Kenyan fans, Mahmoud Abbas was Kenya One. But to Tanzanians, he was golikipa mchawi – the goalkeeping wizard. This term, coined by their colourful football commentators, carried a fine blend of awe, respect and detestation.

There was something to the character of Abbas that made this perfectly understandable. He was both an outstanding goalkeeper and a showman, engaging both players and fans in theatrics. Depending on his mood, which was almost always good, he would clap cheerfully for forwards whose shots he had saved with ease. He used to accompany the claps with a broad grin. Some players found this sarcastic compliment unbearably aggravating, especially coming after they had put everything into their efforts. But they invariably held their peace; clapping was no foul play as far as the rule book went.

He was a darling of the fans, many of whom proclaimed him Kenya’s best goalkeeper ever. This was highly subjective, of course, as Kenyans of an earlier generation prefer to bestow this accolade on James Sianga. What is not in doubt, however, is that he was an exceptional talent whose fame spread beyond Kenya and went across the African continent.

In Hopes and Dreams, Abbas features alongside fellow Kenyan legend Joe Kadenge. His citation reads: “He is undoubtedly one of those players who have influenced a whole generation of African stars. He will be remembered for his ability to save penalties. His place in African football folklore (is) assured. He is a footballing legend and will always be one of the best African goalkeepers ever.”

It is a tribute to his special gifts, by which he dominated the space between the posts for more than 10 years at a time when Kenya didn’t have a shortage of goalkeeping talent.

Men like Mohammed Magogo, the captain he dethroned, Dan Odhiambo, Gor Mahia’s number one, and Washington Muhanji, the soldier from Lanet’s Scarlet FC, were all great goalkeepers. They were also all called for national duty. But Abbas locked them out and reigned to the end, forever banishing their status to the footnotes of Harambee Stars history.

There are many qualities he brought to the game, but some stand out. He had an unusual dedication to training and fitness and worked with weights when many of his colleagues were content with field training only. It is a quality too overt to modest about.

“I think only three of us worked with weights consistently – Swaleh Ochieng Oswayo, Wilberforce Mulamba and myself.”

The weights must have worked wonders for his hands. He preferred to throw the ball to his team mates after making a save rather than kick it. His throws comfortably passed the half way line and were remarkably accurate. And he had a big mouth to go with it. You could hear him shout his teammates’ names from the stands, especially during the anxious moments that go with constructing an anti-free kick defensive wall.

When Harambee Stars went to Dar es Salaam for the 1981 East and Central African Challenge Cup, Tanzania was in the grip of a biting shortage of all essential items, food being at the top of the list. Relations between the two countries were at an all-time low. Tanzanians labelled capitalist Kenya a man-eat-man society – nyang’au (hyenas) – and Kenya responded by calling its socialist neighbour a man-eat-nothing society.

When a large group of Kenyans arrived in Entebbe aboard a flight specially set aside by Kenya Airways for fans to cheer Harambee Stars, they found a desperate, unhappy country. The buildings at Entebbe terminal still bore pockmarks, graphic evidence of the artillery shells that had finally driven out Amin

Abbas used the game against Taifa Stars to showcase Kenya’s prosperity. In one of the preliminary matches, he threw six pieces of Lux toilet soap at the Tanzanian fans massed at the terraces of the National Stadium. Soap was one of the scarcest items on Tanzanian shop shelves and there was a stampede to pick up the rare treasures.

Commentators screamed blue murder at his effrontery. But this was not the impudence that gave rise to the moniker “golikipa mchawi”. There seemed to be an element of the supernatural to quite a number of Abbas’ performances.

Before Kenya and Tanzania lined up for the final of the Challenge Cup on that bright afternoon in November, Abbas had a long conversation with Coach Marshall Mulwa. “For most of the day, we sat together, just the two of us,” says Abbas. “’Captain,’ he said to me, ‘you don’t know how good you are. Nobody can beat our defence. Last year, we played well but we lost because we had a very young team. But now we are a lot more mature.’”

As game time neared, Mulwa issued his instructions to Abbas. “You will win the toss. And when you do, I want you to select the side of the goal where you conceded five goals last year. Do that, and I am assuring you we are going to win the Cup today.”

Kenya had the previous year been hammered 5-0 by Taifa Stars in a World Cup qualifying game, with all goals being scored in one end. And it was Abbas who had conceded them. Mulwa wanted Abbas to start in that goal after winning the toss. The goalkeeper asked his coach, “Suppose I lose the toss?”

“You won’t!” Mulwa said. “I am telling you, you won’t lose the toss. Just do as I tell you!”

He was both firm and persuasive.

And so Abbas went for the toss without any instructions on what to do if he lost it. He, however, retained all his faith in the coach. The referee flipped the coin in the air and, voila! Just as Mulwa had predicted, Abbas won the toss. He selected the designated goal.

“There was a strong wind blowing from the direction of the sea,” he recalls. “This wind blew a huge polythene bag, such as the one used to cover a bale of unga, into the goal I had selected. The bag travelled such a great distance into the goal without anybody stopping it that it instantly became the subject of much talk among the superstitious Tanzanians.

“I picked it up from the back of the net and threw it at the crowds. Suddenly, I heard shouts of “Mchawi! Mchawi! Mchawi!” (Wizard! Wizard! Wizard!). To my knowledge, that is when I became the goalkeeping wizard thanks to our good Tanzanian neighbours.

But I don’t believe in witchcraft. I don’t believe it works.”

Tanzania played the game of their lives. Their marksman, an exceptionally skilled and lanky man called Peter Tino, pulled every last trick in his bag but, as Abbas remembers, “Bobby neutralised him.” Bobby Ogolla, the Six Million Dollar Man, was Kenya’s stopper and a particular favourite of Abbas.

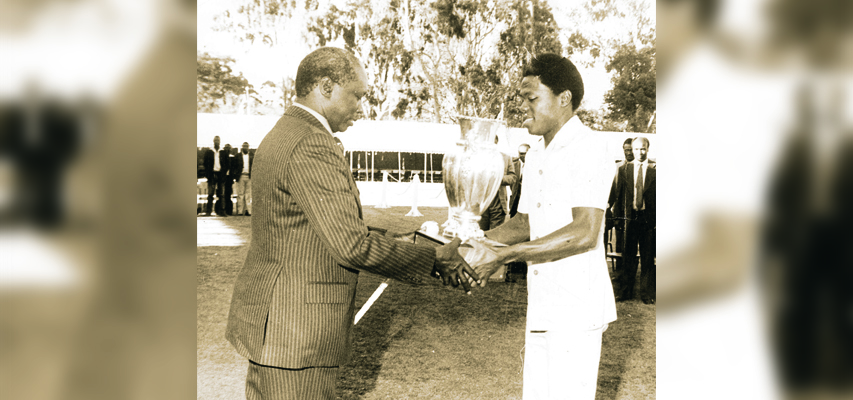

Kenya won the game 1-0 and Abbas lifted the Challenge Cup in the first of three consecutive runs before a multitude of crestfallen home fans. This is when the legends of Mahmoud Abbas and Coach Marshall Mulwa seriously begun.

Kampala, November 1982

Abbas’ legendary ability to save penalties came to international notice during the 1982 East and Central African Challenge Cup tournament in Uganda. It started in Jinja’s Bugembe Stadium in a tightly contested semi-final match between Kenya and Zimbabwe. Abbas recalls the proceedings with great relish and candour. “It was my mistake,” he says of the penalty Harambee Stars conceded to Zimbabwe. FIFA, football’s world governing body, had recently enacted a rule meant to clamp down on goalkeepers who wasted time when their teams were leading. This rule followed the 1982 World Cup which Italy won in part because Dino Zoff, their goalkeeper and captain, specialised in running out the clock during the dying minutes of their victorious matches.

“The score was 2-1 for us against Zimbabwe. I picked up the ball and bounced it twice on the ground instead of once. The referee, Said Ali from Zanzibar was lenient; he let it pass. But when I did it again, he immediately awarded an in-direct free kick against us. It was about six yards from the goal line. Joel Shambo’s shot was definitely goal bound but J.J. (Masiga) openly and deliberately stopped it with his hands.”

The penalty was promptly awarded.

“I told J.J., ‘Thanks, and don’t worry, I’ll deal with it’.

“Dave Mwanza stepped forward to take the penalty for Zimbabwe. I stood a foot or so in front of him as he carefully placed the ball on the spot. As he lifted his head, I looked into his eyes. I saw him look to his right and there and then, I knew in what direction he would shoot. His eyes said what his mind had decided. I took my place on the goal line. The shot came and I flung myself to my left. I saved it!”

This set the stage for the epic final between Kenya and Uganda in Kampala’s Nakivubo Stadium. For 15 years, the Ugandans had not lost a Challenge Cup final at home. But there was more to this game than records. When nations of Kenya and Uganda came were created, the gods must have decreed that football matches between Harambee Stars and Uganda Cranes would never be ordinary. Each one of them, generation after generation, was going to be a grudge match. There has never been any such thing as a friendly between the two sibling states, which hope to federate into a single country someday.

In 1982, this rivalry peaked. At that time, Uganda was in the grip of a low intensity civil war. In 1979, finally tired of Idi Amin’s murderous regime, which had twice made military incursions into his country, President Julius Nyerere had sent the Tanzanian Army into Uganda to rid it of the tyrant.

The Tanzanians had arrived at the head of a motley collection of Ugandan exile groups whose only point of agreement was their opposition to Amin. Once in power, they turned on each other. Even by its own standards of chronic political instability, the country was going through a dreadful period known as Obote II, denoting the second coming of its Independence President. Obote had been rigged back into power and he faced a plethora of enemies, many of them committed to violently dethroning him. There had been rumours he might attend the match but, in the end, he stayed away.

When a large group of Kenyans arrived in Entebbe aboard a flight specially set aside by Kenya Airways for fans to cheer Harambee Stars, they found a desperate, unhappy country. The buildings at Entebbe terminal still bore pockmarks, graphic evidence of the artillery shells that had finally driven Amin away.

Every staff member at the airport seemed tense and preoccupied. Kenyan fans tried to chat them up, but it didn’t work. The Kenyan seemed to have come to a wedding party while the Ugandans appeared to be arranging a funeral – many of them sang Mwana wa mbeli the AFC Leopards anthem.

The merry Kenyans got into chartered buses and headed for Kampala. Standing at the front and back of each bus was a soldier armed with an AK47 rifle. The soldiers were there to protect them in the likely event of an ambush along the highway. Unlike the fans, the soldiers spotted faraway looks in their eyes, completely oblivious to the party swirling around them.

Before the buses got into Nakivubo, and unbeknown to the fans, a piece of drama was unfolding there. When the bus carrying Harambee Stars arrived at the stadium at about 2 p.m., Coach Marshall Mulwa flatly refused to allow the team to enter the stadium through the main entrance.

Despite intense entreaties by Ugandan officials, he insisted on going through a small gate that had not been used for a long time. The stand-off lasted about one hour until finally, exasperated, the Ugandans gave in. The gate was very small and the players, technical staff and accompanying journalists left their vehicle outside and walked in. Mulwa offered no explanation for his intransigence, but he seemed quite satisfied with its result.

The previous day, he had upset Ugandan fans – and possibly some Cranes technical spies – when he brought his charges to Nakivubo in what was the Kenyans’ last training session. The locals had expected to see the fluent moves that had brought Harambee Stars to the final; instead, Mulwa decided that the entire session was to be dedicated to penalty shoot-out practice.

By this time, Abbas’ prowess in this specialty was well known. Still, the Ugandans were left scratching their heads when out of 15 shots, Abbas saved only five while his substitute keeper, Washington Muhanji, stopped ten.

The Ugandans couldn’t figure out Mulwa’s psychological games.

The travelling fans arrived at Nakivubo just in time for kick-off. Scarcely had they settled for the game than they were jarred by explosions outside the stadium. Billows of smoke rose in the air behind the walls. Soldiers ran helter-skelter. But the game started and went on uninterrupted. It seemed, in the face of extreme danger, Ugandans had somehow devised a way of shutting it all out and going about their lives as normally as they could.

This final was a match like none the two rivals had played before. Their tactics were a study in contrast. Marshall Mulwa based his strategy on a defence made out of granite. Josephat Murila and Bobby Ogolla in the centre and Peter Bassanga Otieno and

Hussein Kheri in the flanks perfectly anticipated the best moves their opponents could conjure. The team’s breakaway moves in counter-attack were a thrill to watch because of the speed of forwards such as Mulamba, Masiga and Ellie Adero.

And then there was the player who had adopted a style of his own. Ambrose Ayoyi played competently on both wings, although his left foot was a tad stronger and more accurate in delivery of canon ball shots. Ayoyi specialised in losing his markers.

Somehow, he was able to hide in the open and markers only remembered him when he had either caused their formations damage, or was about to. Cranes paraded their best team since the incomparable squad of 1978 when they lost the Africa Cup of Nations final against Ghana. In fact, there were a few remnants of that magnificent squad. The Cranes played total football and anybody who was not a Kenyan fan must have been on their side. It was difficult to think of a neutral in the crowd that day.

Some of the greatest names in their football history – Paul Hasule, Moses Nsereko, Philip Omondi, John Latigo and Issa Sekatawa – were there that day. This team attacked and defended as a unit, just as Holland memorably did in the 1974 World Cup finals in West Germany. To see John Latigo, right full back, in full cry across the right wing and into Harambee Stars penalty territory was simply spellbinding.

Rallied on by their multitudes of supporters, the Cranes attacked in waves, one after the other. It was an epic duel pitting defence and attack.

The faith the Kenyans had in themselves against any forward line was aptly captured in a remark Hos Maina overheard Josephat Murila make during the successful campaign in Dar es Salaam the previous year. According to Hos, Murila had told the forwards, “You guys, just score one goal and leave the rest to us.” In Nakivubo, the forwards did just that, with the powerfully-built midfielder, Wilberforce Mulamba dribbling all the way from the centre to rifle in a spectacular goal.

Uganda played the game of their lives in response, and most of the game happened in the Harambee Stars half of the pitch. Still, the Kenyan defence held. But matters came to a head when the Malawian referee, Billie Pambala, hesitantly awarded the Ugandans a goal after the ball had slammed the underside of the crossbar and ricocheted on the goal line before Ogolla cleared it away.

Even the Ugandans weren’t sure it had crossed the line. Their celebrations were not spontaneous. The Kenyan players hotly disputed the decision and, led by Abbas, walked off the pitch. So emotional was Abbas that he broke down and refused to return to goal. In touchline melee, it took an eternity for the combined efforts of Kenya’s Culture and Social Services Minister Paul Ngei, Coach Mulwa, team manager Apollo Ndenda and even some Stars players themselves, led by Murila, to persuade Abbas and company to play on. The match tottered on the brink of abandonment, a decision the referee would have been obliged to make after 10 minutes of stoppage. In the end, cooler heads prevailed.

The Ugandans had a powerful motivation to win the game within regulation time: Mahmoud Abbas and the dread of a penalty shoot-out. The Cranes knew that if the game came to this, they would be walking in the shadow of death. To compound this doomsday prospect, Kenya had high quality marksmen of its own. So the Ugandans attacked and attacked. Every passing minute brought more urgency – and desperation – to their endeavour.

But their efforts came to nothing. The score at full time and extra time was 1-1. The match went into penalties. Death beckoned. Abbas stood in regal and arrogant splendor between Kenya’s posts and the worst fears of the Cranes and their country came to pass.

He stopped two penalties, had a third perfectly covered on its flight over the cross bar and Kenya won the Challenge Cup for the second year running, and an unprecedented fourth time. Uganda’s 15-year record of not losing a final at home lay shattered.

In the Kenya Airways plane back home, the pilot, a Captain Gatheca, declared that in celebration of Stars’ great victory, all drinks on board were on him. He was a big Stars fan. As the airline’s deputy Chief Pilot responsible for, among other duties, crew scheduling, he had assigned himself that flight to witness first hand Stars defend their title. Now, with mission accomplished, he was profuse in his tribute to his countrymen.

The entire Kenya Airways crew had been at the stadium for the match, seated on the grass by the touchline. In the cabin on the way home, I asked one of the stewardesses what she thought of the match and she burst into a rhapsody: “Oh, he saved us! He really, really saved. He’s such a brave man. He never allowed them to pass us. He is the one who saved us!”

“Who saved you?” I asked.

“The injured man! He is very, very brave. He is the one who saved us.”

The injured man, of course, was Ogolla. The Six-Million-Dollar-Man had suffered a cut above his right eye during the match. It was stitched and bandaged right there on the touchline, but the dressing kept coming off – Bobby, the kingpin of defence, alternated between play and treatment for the rest of the match. In the end, his shirt was soaked in sweat and blood. It was easy to understand the star-struck air hostess.

Seated next to his coach on the plane, Bobby swigged one tot of whiskey after another until Marshal turned to him in mild alarm.

“Bobby, enough of that,” the coach said, “You have not eaten.”

Bobby smiled generously and praised his coach. Then he ordered one last tot and started rhythmically bending his elbow. It was, of course, not the last one. The long campaign over, he was deservedly unwinding, and as a true hero of the tournament, no one could begrudge him his indulgences.

Even Mulwa had to look the other way.